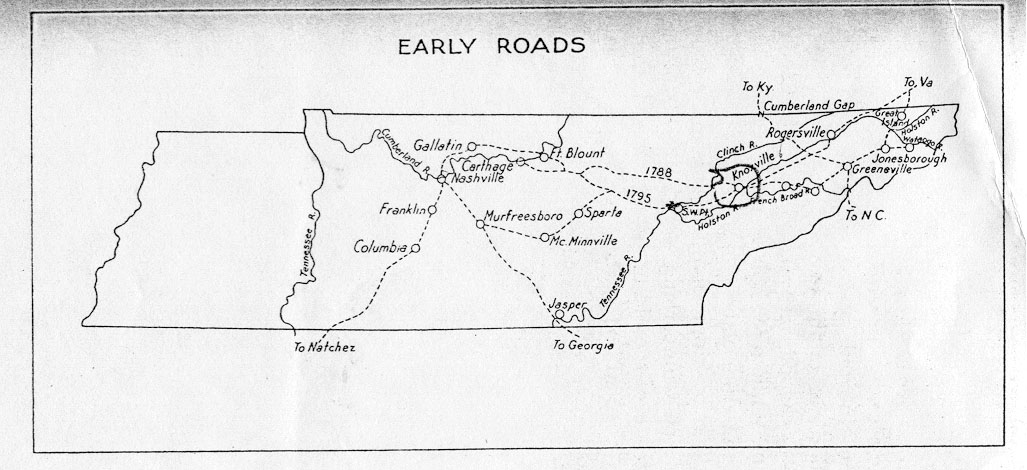

Figure 1 Map: From Frontier to Plantation in Tennessee by Thomas P. Abernethy

The Emery Road followed closely some sections of the path of an old Indian trail from the area now known as East Tennessee to what is now Middle Tennessee. This worn path was known as Tollunteeskee’s Trail. Long Hunters used portions of this trail as early as 1766 when James Smith returned from a long hunt using the route. James Robertson’s overland trip in 1779 to establish the Cumberland settlement at present-day Nashville used the more circuitous route of The Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky and south to the Cumberland River. As this route did not cross Cherokee land, it was safer for travel than the more direct route, even if it was longer. Robertson’s use of the more established route through Kentucky indicates that the route that came to be known as the Emery Road was not yet well established in 1779.

The Cherokee claimed the territory between the Clinch River and a treaty line west of Standing Stone – modern day Monterey. They disputed the right of the white settlers to use this trail through their country without permission. The use of trails, blazing of “traces,” and cutting of roads through their land without payment was one of the reasons provoking a long and bloody war between the Cherokee and white settlers and was a constant subject included in all treaty negotiations. The Cherokee always insisted that the government build “one road” from Washington District to the Cumberland settlements, rather than many traces using various routes.

In 1786, when Captain James White built a station at the junction of the Holston and French Broad rivers that join together to form the Tennessee river, James Robertson and a handful of other men spent seventeen days clearing a more direct route than the Wilderness Road – a pack-horse trail across the plateau and mountains from Fort Nasborough (Nashville) to Captain James White’s station (Knoxville). This clearing effort followed generally the route later blazed by Peter Avery in 1787 as a result of an act passed by the North Carolina legislature.

The first formal authorization to "cut and clear" a trace for a direct route to the Cumberland settlements occurred in 1785 when the North Carolina legislature provided for a force of 300 men to protect the Cumberland settlements. These soldiers were charged with cutting and clearing a road, by the most eligible route, from the lower end of the Clinch Mountain to Fort Nashborough (Nashville). More direct and shorter than the Wilderness Road, it would accommodate expected increases in immigration as Revolutionary War veterans claimed their land warrants. Probably little real progress was made on this road as James Robertson continued to request protection and improvements.

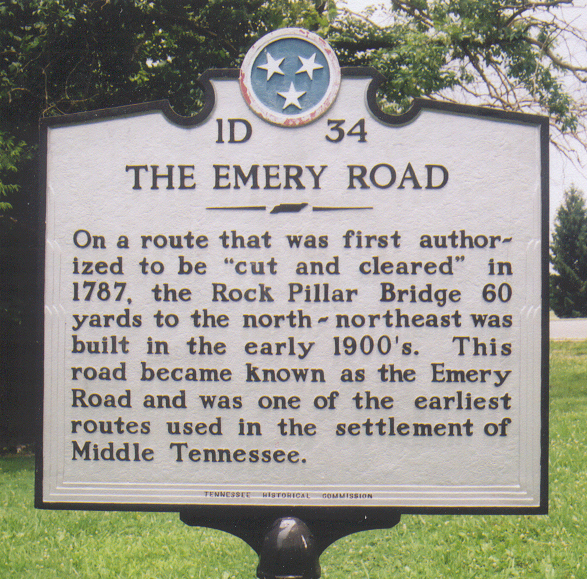

In 1787 North Carolina legislators approved a second road act, which again ordered a road cut and cleared from the south end of Clinch Mountain to Fort Nashborough (Nashville). Peter Avery blazed a trail beginning at the south end of the Clinch Mountain at present-day Blaine. The Avery Trace as it was later known marked the route that closely followed where the present route of Emory Road in Knox County is now located. The original route crossed the Clinch River at Lea’s Ford near present-day Oak Ridge at the marina and continued through the middle of present-day Oak Ridge passing near the Oak Ridge High School where an existing rock bridge constructed just after 1900 was located on the old route. The road then passed through Winter's Gap (Oliver Springs) and crossed the Emory River near present-day Wartburg. It passed through present-day Lansing to Johnson's Stand, followed a ridge to Standing Stone (Monterey), and then went on to the Cumberland settlements (Nashville). Major George Walton directed the soldiers working on this earliest road. This route was known at various times as Avery's Trace, the old North Carolina Road, and Emery Road.

The Cherokee continued to resist white settlers crossing their land and demanded that tolls be paid. Those who refused risked losing their lives. A concern for safety caused individual travelers and families to avoid the northern route and form groups on the banks of the Clinch River to wait for an armed escort by a more southern route that joined the northern route near present-day Crossville. Both routes were still little more than traces, yet Harriette Arnow noted that a party of 100 under the protection of Kasper Mansker and other guards used the trace in 1787, a year before it officially opened.

In 1788 the North Carolina legislature passed a third act for a road to the Cumberland settlements and provided for two companies of militia of 50 men each to guard immigrants. When the road (southern route) was completed, Robertson gave notice in the State Gazette of North Carolina that soldiers had successfully escorted the first party of immigrants on September 25, 1788. During that year several families grouped together and made the escorted trip, including the widow of General Williams Davidson and Judge John McNairy and his family. Andrew Jackson also came to the Cumberland settlement during the period, having obtained an appointment as prosecuting attorney.

James Robertson continued to petition the North Carolina legislature for improvements to the trace. His pleading went unanswered until 1788 when an act was passed instructing that a road be cut and cleared. This “road” actually developed into a system of roads or paths that generally followed the driest route and might be changed frequently as attacks by the Cherokee made some sections unsafe and new routes were chosen. Stations were formed along the route that served to provide protection and shelter for the travelers. The system of roads continued to evolve until the summer of 1795 when a wagon road was opened from Knoxville to Nashville, direct, so that loaded wagons could pass. The more southern route was used for this improvement and become the route most travelers chose as it was the most protected and heavily traveled.

The system of roads came to be known as the Emery Road and served travelers exclusively for ten years (1785 – 1795) as the primary route of travel. The Emery Road continued to be a part of the network of early wagon roads. Later improvements to the route through the years kept it a main thoroughfare.

An existing concrete and rock bridge located on the later and improved route of the original Emery Road is recognized by a marker located just northwest of the Oak Ridge Turnpike near the Robertsville Road intersection.

An existing concrete and rock bridge located on the later and improved route of the original Emery Road is recognized by a marker located just northwest of the Oak Ridge Turnpike near the Robertsville Road intersection.

This historic marker records a later improvement to the original Emery Road that had crossed the Clinch River at present day Melton Hill Marina in Oak Ridge.

The route most likely taken is close to the present day Emory Valley Road that runs from the river at the marina toward the center of Oak Ridge. The road likely continued west and may have taken any of a number of varying routes such as crossing Black Oak Ridge and going through Winter's Gap (present day Oliver Springs) or passing on down East Fork Valley to cross Black Oak Ridge at Clack's Gap. Any of these likely routes might have preceded the others and would have been developed as settlement of the area increased.

The Emery Road bridge is just northeast of the Midtown Community Center, home of the Oak Ridge Heritage Preservation Association. This structure is a Manhattan Project era historic building that was first used as a Community Center and later as the "Wildcat Den" for youth activities. It is an example of one of the several structures that represent Oak Ridge history and is most deserving of historic designation.

A much earlier structure, the David Hall Historic Cabin, constructed prior to 1799 was also located on the early route that came to be the Emery Road. This cabin has an interesting history. The current owners are  Harry and Libby Bumgardner (Libby is the grand daughter of the third owner of the David Hall cabin - Walter and Nannie Thomason). The cabin is located east of the Clinch River near present day Claxton, TN. In the early years, David Hall operated the two cabin complex as an Inn and Tavern. It served this purpose through the Civil War. The last persons to live in the cabin were Rova, a daughter of Nannie Thomason and her three sons. They moved out of the cabin in 1976.

Harry and Libby Bumgardner (Libby is the grand daughter of the third owner of the David Hall cabin - Walter and Nannie Thomason). The cabin is located east of the Clinch River near present day Claxton, TN. In the early years, David Hall operated the two cabin complex as an Inn and Tavern. It served this purpose through the Civil War. The last persons to live in the cabin were Rova, a daughter of Nannie Thomason and her three sons. They moved out of the cabin in 1976.

Libby has taken an intense interest in restoring and preserving the historic cabins. She has also found a large cache of paper documents in a large trunk kept in the upstairs of the two story main cabin. Evidence of Civil War activity is found there as are other 1800's era receipts, letters and other documents. She is doing a wonderful job maintaining the history of the cabins. These cabins are representative of many such Inns and Taverns that existed along the early Emery Road.

D. Ray Smith - 9/11/05

Reference information for this article has been taken from the following sources:

1. Corlew, Robert E. Tennessee, A Short History. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

2. Durham, Walter T. Daniel Smith Frontier Statesman. Gallatin, TN: Sumner County Library Board, 1976.

3. Parks, Joseph H. and Stanley J. Folmsbee. The Story of Tennessee. Chattanooga, TN: Harlow Publishing Corporation, 1958.

4. Ramsey, J. G. M. Ramsey’s Annals of Tennessee and Fain’s Index. Kingsport, TN: Kingsport Press, 1926.

Other Oak Ridge, Tennessee Links:

American Museum of Science and Energy

Oak Ridge Convention and Visitor's Bureau

Historical Markers in Oak Ridge

Oak Ridge History

Secret City History

Hymn to Life

John Hendrix and Y-12

Back of Oak Ridge and John Hendrix (Prophet of Oak Ridge) book

Secret City The Movie

Calutrons - Plowshares Story

Bear Creek Valley

The Calutron Girls

Please send any questions, comments or suggestions about this page to Comments